Key Takeaways

- All sunscreen negatively affects the environment, but chemical sunscreens are more harmful

- Chemical sunscreens are quickly losing share, in part due to bans in certain jurisdictions, e.g., Hawai’i

- Mineral Sunscreens and “Reef Safe” labeling drive growth; shoppers are looking to minimize environmental impact

Introduction

Mineral and chemical sunscreens perform the same function—protecting skin from harmful UVA and UVB rays that cause short-term (sunburn) and long-term (skin cancer) damage—but they do this in different ways! However, both cause negative environmental impacts.

As values-oriented shoppers continue to investigate how their choices impact the environment, it’s crucial for brands and retailers alike to understand how their assortments deliver against those values.

Mineral vs. Chemical Sunscreens

As our world grows warmer and exposure to more intense UV rays for longer durations throughout the year becomes more common, shoppers are taking a closer look into sun protectants, like sunscreen, and how they affect the environment.

Broadly speaking, there are two primary types of sunscreens: mineral and chemical. Mineral Sunscreen uses titanium dioxide and zinc oxide or a combination of the two to block UV rays from penetrating your skin and causing damage. When applied, they sit on top of the skin and deflect the incoming UV rays away. This type of sunscreen does not absorb into the skin and, as a result, is typically characterized by leaving a white film.

Chemical Sunscreen, on the other hand, uses several different chemicals—avobenzone, oxybenzone, octinoxate, octocrylene, homosalate, and octisalate—to prevent UV rays from damaging your skin. These chemicals absorb into your skin while also absorbing UV rays. As a result, it behaves more like a moisturizer without leaving a white film.

Why Mineral vs. Chemical Sunscreens Matter

It’s important to note that both types of sunscreens have negative environmental impacts. Mineral sunscreens are less harmful, but—like chemical sunscreens—they still have compounds that contribute to a phenomenon known as bioaccumulation.

In this scenario, bioaccumulation occurs as humans apply sunscreen and then go into the ocean (or other naturally occurring bodies of water) or rinse it off in the shower. While sunscreen isn’t toxic when used as directed by humans, when these chemicals wash into water, they accumulate in the smallest marine organisms—krill, mollusks, coral, etc.—and gradually make their way up the food chain, increasing in concentration along the way.

This causes a wide variety of negative side effects such as:

- Impaired growth and photosynthesis of algae

- Accumulation in coral tissue causing bleaching, DNA damage, and deforming and killing young organisms.

- Defects in young and growing mussels and other mollusks

- Damaging immune and reproductive systems as well as deforming sea urchins

- Decreased fertility, damaged reproductive systems, and genetic mutations in fish

- Accumulation in the tissues of larger ocean/aquatic animals such as dolphins, sharks, and whales that consume smaller organisms

While sunscreen in our aquatic ecosystems affects several animals, one of the most high-profile examples are coral reefs. Coral reefs are some of the most sensitive and valuable resources on the planet—they contain up to 25% of the ocean’s marine life with an estimated 4,000 species of fish. As few as three drops of oxybenzone mixed into an Olympic-sized swimming pool can damage coral larvae! To respond to these negative externalities, the values-oriented shopper is starting to pay more attention to what kinds of sunscreens they’re applying to make sure what they’re applying is not only good for their health but also minimizes their environmental impact.

Values-Oriented Shoppers are Reshaping Sunscreens

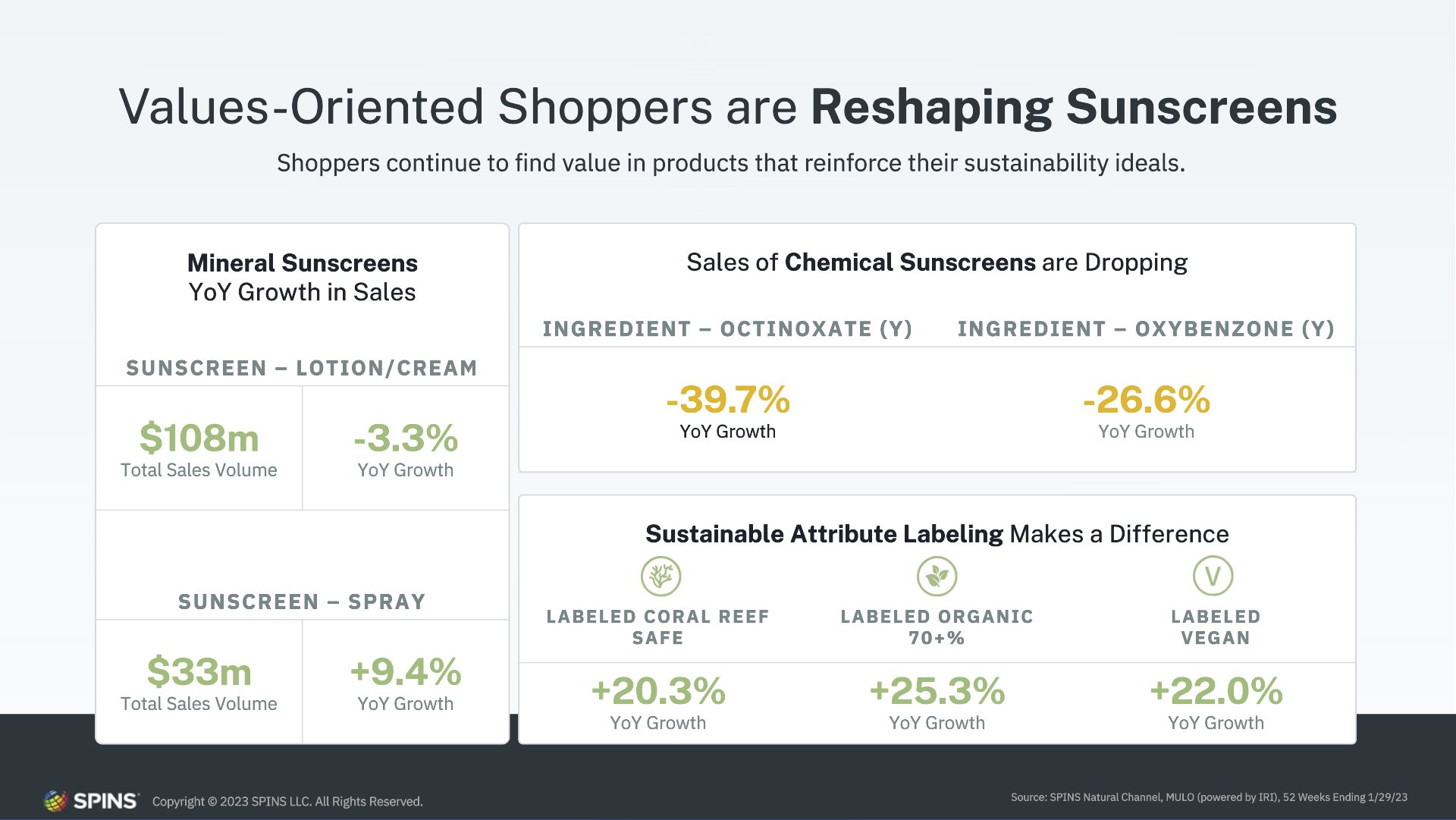

When we look at the data, it’s clear that shoppers are starting to move away from the worst of chemical sunscreens and that sustainable attributes are starting to drive growth. While we’re not seeing the absence of chemical sunscreen agents making a major impact in sunscreen lotions and creams, we are seeing it have a major impact in sunscreen sprays, with 9.4% percent growth as compared to -9% growth for sunscreen sprays that do contain chemical sunscreen agents.

We’re also seeing striking declines in the chemical sunscreen agents that are often targeted as being the most damaging to the environment – octinoxate and oxybenzone: -39.7% growth for octinoxate and -26.6% growth for oxybenzone. This suggests that both shoppers and brands are responding to calls for more sustainable sunscreen products.

Finally, we have a few more SPINS sustainability attributes to help tell how sunscreens are promoting sustainability in other ways. By taking a look at the Labeled Organic attribute, we see sunscreens leveraging 70% or more organic ingredients resonating as well as sunscreens leveraging vegan, cruelty-free practices, both of which are great ways to reinforce sustainability ideals for shoppers.

Conclusion

While all sunscreens have negative environmental impacts, everyone needs sunscreen! To mitigate damage and protect our planet, shoppers are starting to choose more environmentally friendly options—namely mineral sunscreens containing titanium dioxide and zinc oxide. Due to the harmful effects of certain chemical sunscreens, they have been outright banned in Hawai’i. However, the ban notwithstanding, the data shows that shoppers are increasingly choosing sustainably positioned sunscreens.